First off, congratulations on applying to dental school! Someone’s teeth and smile can change their whole way of interacting, feeling, even just being. That you are investing your skills to ensure that their smile can be a carefree one, well, that’s good, important work.

But first, you have to get over the hump of writing your dental school personal statement. I’d be honored to give you a few tips. Let’s begin:

YOUR PROMPT

Most dental schools participate in the Associated American Dental Schools Application Service (AADSAS), which means you fill out one application and send it to the dental schools to which you’re applying.

In that application, you have 4,500 characters to work with for your personal statement, which roughly translates into a single-spaced page of writing. Be aware that spaces and punctuation count toward your character count.

In your personal statement, according to the AADSAS, you want to give “dental schools a clear picture of who you are and, most importantly, why you want to pursue a career in dentistry.”

So, essentially, your personal statement should answer: Why do I want to be a dentist? Or, if you like, what about me will make me a good dentist?”

START WITH TWO LISTS

Before you begin writing, I want you to make two sets of lists. Yay, lists!

First, I want you to list what traits you possess that would make you a great dentist. Are you:

- compassionate

- a good communicator

- empathetic

- motivated

- a leader

- caring

- a good listener

- persistent

- intellectually curious

- humble

For more about the traits a good dentist should have, click here.

Next, I want you to make a list of your:

- “aha” moments (moments of sudden insight or discovery)

- passions/interests

- drives

- regrets

- challenges

Whittle down these lists so that each of them contains three strong traits of yours and three of your passions/drives/challenges/”aha” moments, etc.

Then I want you to think of the stories that demonstrated times when you felt most passionate/regretful/driven/aha’ed and what traits those moments triggered in you.

The goal here is to get one solid story that helps encapsulate what kind of person you are.

NO STORY IS TOO SMALL

For personal statements, the best stories are honest, detailed, show vulnerability, and go somewhere. Try to zero in on a truly important moment in your life, something that has helped define you and led you toward the path you are now trying to pursue.

Don’t worry too much if it doesn’t seem that interesting or unique from the outset; the key is that it was important to you. It can be about the day you volunteered at a day camp for kids with special needs. It can be about a day in the park when someone fell off their bike. It can be about the day in the park when you fell off your bike. It can be about someone choking on a waffle in a diner. It can be about cooking with your grandfather. It can be about figure skating. It can be about playing the violin. It can be about swimming in a lake. It can be about pushing a wheelchair. It can be about being in a wheelchair.

Thinking of this story, I want you to activate your senses. What did you see? Hear? Taste? Feel? Smell? What are the littlest details that you remember about it? What were you wearing? The person beside you wearing? What did the concrete feel like? The water feel like? What were you cooking? Playing? What did you smell?

Know that no detail is too small. In fact, I want you to activate the mundane intentionally. Life’s littlest details are exactly what is going to make this story uniquely yours. Why? Only you noticed something so small and detailed. That is what will make your story authentic.

WRITE ABOUT WHAT YOU DID

Once you’ve zeroed in on your story, I want you to write about your place in the story. How did you behave in the moment that you’re describing? What did you do? What did you think? How did you react? How did your brain work? How did you tackle?

Here is the point where I want you to show your vulnerability (and if that gives you the heebie-jeebies, too bad: go there). You need to let the reader know what role you played in this moment and what you realized and learned and thought and how all of that changed you.

One important point: You don’t have to be the hero. In fact, it’s probably better if you aren’t. It’s been my experience that “aha” moments that help define one’s life are often shockingly small in nature.

Another important point: If your moment intrinsically involves someone else, say your grandfather or your mom, or something else, like a trip or an event, you must constantly be careful to make the essay about you reacting to your grandfather, mom, trip or event. It cannot actually be about your grandfather, mom, trip or event, OK?

WHAT TO WRITE ABOUT AFTER YOUR OPENING STORY

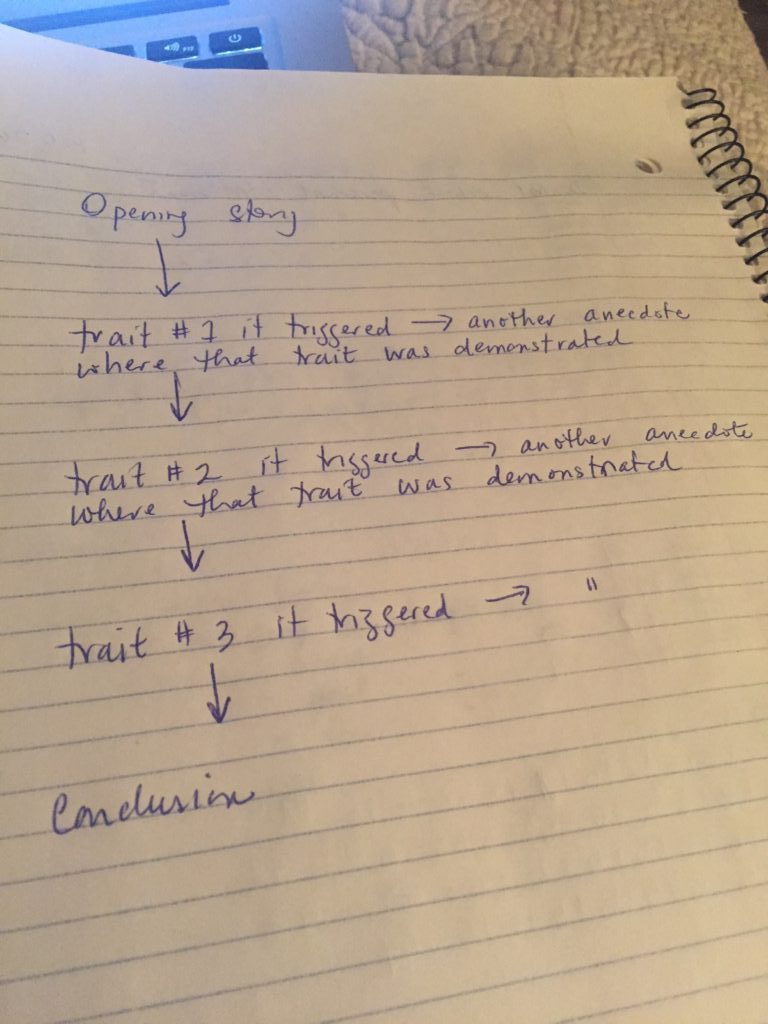

Remember your lists? And that I had you isolate three traits and three passions/drives/aha moments? That wasn’t for nothing. After your opening story, I want you to write about the other reasons why you want to go into dentistry and, likewise, tie them to short anecdotes that demonstrate both your traits, “aha” moments and what you did in those moments. Obviously, these will be less detailed than your first story, but they will show different aspects of why you want to be a doctor.

WHAT NOT TO WRITE ABOUT

There are stories I think you should avoid. A story about a 6-year-old you “cleaning” your Barbie’s teeth is one. I don’t care how many details you add to that story, it’s just been played out. Same for the story of a 7-year-old you being entranced by the oversized toothbrush at the dentist’s.

By and large, I prefer for stories to be about the adult you, rather than the kid you. To me, what you have realized as an adult says more about you than what you realized as a child. If there isn’t a way to work around that, that’s OK, if you stick to being honest and rely on the details. It’s also preferable if you are still involved in whatever it is you are writing about. Meaning, if you write about your passion for drawing, it needs to be something you’re still passionate about as an adult.

Further, I strongly recommend you avoid the sentence “I like to help people” in your personal statement. Guess what? Every dentist does. And more than that, liking to help people doesn’t uniquely belong to being a dentist. Teachers help people. Dental assistants do it. Cops do, too.

Finally, don’t be too chronological in your dental school personal statement. You don’t want your essay to be plodding. We don’t need to read about your childhood, then middle school, high school, college experiences. Even if they demonstrate you being consistent about wanting to be a dentist, they don’t show much else. Besides, everyone applying will have these milestones in their lives; they’re not unique enough to write about.

ADDRESS YOUR SLIP-UPS IN YOUR PERSONAL STATEMENT

The personal statement prompt invites you to address gaps that may appear in your transcript, whether you had to take a year off or you failed a class. If you have these slip-ups in your academic record, you should absolutely save some space to address them. Remember what I said about vulnerability and honesty? That’s what is important. In fact, these slip-ups say as much about your story as anything else — and they don’t have to be a bad thing.

Just focus on what you learned because of them. Again, it might be a time to explain the exact moment (another anecdote!) you realized the benefits of a hardship.

HOW TO END YOUR DENTAL SCHOOL PERSONAL STATEMENT

Once you have established what you’re made of and have demonstrated why you’re passionate about becoming a dentist, I want you to answer this in your conclusion:

- What is the significance of what you’ve shown the reader?

- What are its implications?

How to pull this off? Show me what you see for yourself in the future. What, for example, could possibly be your most honored day as a dentist? And how were the seeds of that perfect day planted in your opening story?

Or tell me about a patient you will have and what you will do for her.

Or tell me about how you will be changed.

Or tell me about how you will change your community by being a dentist.

Most importantly, broaden my idea of you and your passion in your conclusion, do not simply restate what you’ve already told me. I know they often tell you to do this in essay-writing seminars, but a restatement is just another way of saying “repeat yourself.” With just 4,500 characters to work with, you don’t have the luxury of that. So expand. Indicate. Send me in the direction you are headed, the direction that you want me to see.

FINALLY …

Know that you already have all the material needed to write an excellent dental school personal statement. Using these tips and tactics will help turn good into great. If you need more help, click here and here. And, as always, don’t hesitate to contact me at tara@swayessay.com.