Not that I want to brag or anything, but Margaret Atwood and I have been spending a lot of time together, and I am pretty happy about it.

I’ve been studying the work of the famous, brilliant and, ahem, Canadian writer my entire literary life. I still remember sitting in Mr. Bailey’s room in grade 10 reading “Death of a Young Son by Drowning:”

“There was an accident; the air locked/he was hung in the river like a heart.”

Shudder. Man, so good.

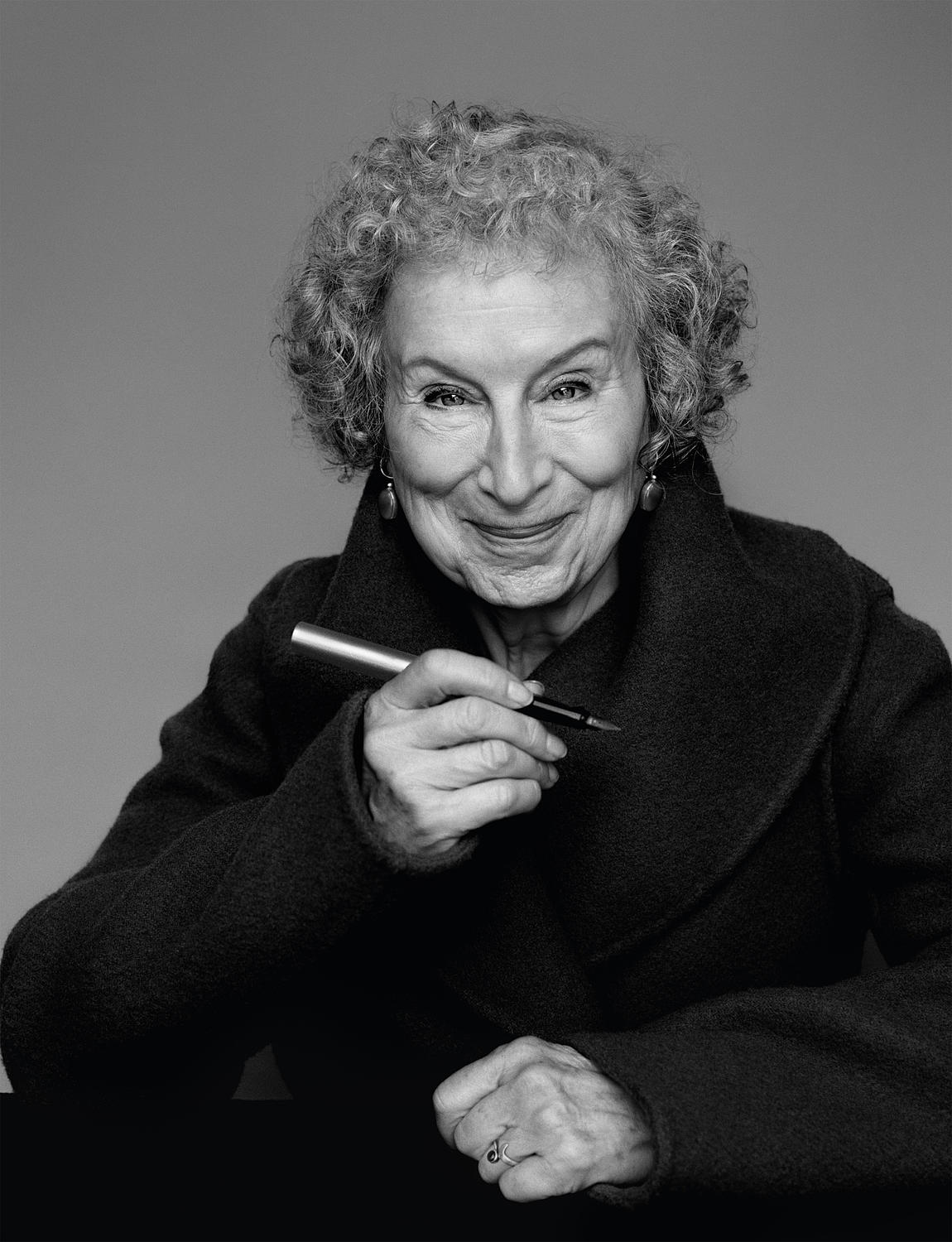

Photo by The Gentlewoman

Anyway, before you think I’m too important, she’s teaching classes on masterclass.com, and I jumped at the chance to learn her methods.

At the same time, since it’s the heart of college essay writing season, I’ve been reading a lot of submissions from students, which involves gently making suggestions and edits. I’ve found that all students, from ones who write ably to ones who struggle with basic mechanics, all commit the same infraction.

They rely on writing that already exists.

ALLOW ME TO EXPLAIN

Let me give you an example. A few days ago, I had a student who opened his essay by painting a picture of a very hot day, which is not a bad place to put a reader who is reading a submission at the beginning of December or January. He started by describing the sun, which likewise seemed like a reasonable decision. But then he wrote, “The sun was beating down on all of us,” and immediately I was bored.

Why bored? How many times does the sun have to “beat down” before we let it do something else? Does it always have to be so abusive? Or if it is, can we not think of a different way to describe its intensity?

Same goes with ideas. Do they always have to go off like a lightbulb? Can’t they be like something else?

Often, we think of clichés as typical phrases that are so over-used that their meaning has been rubbed out:

- “A bull in a china shop,”

- “A bee in your bonnet,”

- “The grass is always greener on the other side,”

- “You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

We all know to avoid employing these phrases. But there is such a thing as clichéd writing, which can be harder to recognize when you’re drafting. It’s any descriptive phrase that you’re using in your work that has been used dozens of times before you. It’s that lightbulbed idea. It’s that beating sun.

So, how to make sure your writing pops in a memorable way? How to make your personal statement stick in the minds of admissions officers? How to write something that belongs uniquely to you?

Let’s turn to Margaret.

CHANGE YOUR VIEWPOINT

In one of her classes, Margaret Atwood talks about the importance of being flexible when it comes to perspective. She uses Little Red Riding Hood as an example. The story is told from Red Riding Hood’s viewpoint. But what if it were re-told from the perspective of the wolf or even that of the grandmother?

“It was dark inside the wolf,” Margaret suggests as an opening line.

Good, right? Eerie. Funky. Memorable.

In your personal statement, the perspective should always comes from your viewpoint, since the point of the essay is to write about you. But the way you set your opening scene can start anywhere.

Let’s get back to the hot day with the beating sun. Let’s say you’re a lifeguard at the local swimming pool. Instead of focusing on the sun, your story can start under the water. It can start in a drop of condensation on the side of a pop can. It can start with the smudge of sunblock on your sunglasses. It can start on an already-wet towel. And the more unexpected (but believable) the place, the better. Because that’s what makes you stand out.

ISOLATE YOUR SENSES

For a while now, I’ve advised painting detailed, honest pictures in your essays by relying on all five of your senses. Ask yourself what you saw, smelled, heard, felt, even tasted. But Margaret Atwood takes it one further. She says another way to get a different perspective is to “block off a few senses and see what the other ones pick up on.”

So, what if you took that sunny day and only relied on your sense of smell? You could describe chlorine, coconutty sunblock, the scent of fabric softener on your towel, the plastic of the unicorn-shaped float a richie-rich kid brought and wouldn’t let anyone else float on. You could describe the scent of french fries from the snack bar, what a popsicle smells like as it’s dripping down your wrist.

All of this allows you to describe a day, paint your picture, in a way that makes your writing stand out. Imagine an admissions officer coming out of her office declaring, “I just read a scented essay.”

It sure beats a beating sun, right?

CHOOSE YOUR VOICE

In her online classes, Margaret Atwood also talks about two kinds of writing: plainsong vs. baroque.

Plainsong is straightforward, often presented in declarative senses, and composed of mostly verbs and nouns (think: Hemingway).

Baroque is adorned with adverbs and adjectives and lots of description (think: Dickens).

As you write, it’s your chance (and your right) to choose what kind of writing to use to convey yourself to the world. Are you in love with adjectives? Do you have an impressive command of the language? Or are you more grounded by function and logic? Do you find flowery language annoying?

Either way, there is opportunity for beautiful writing. The trick is to use the right amount of description to make your personal statement pop. As a rule, in a 650-word essay, I suggest two, a maximum of three, metaphors and/or similes in your opening story.

I know it’s probably pretty un-Atwoodesque to put a number on it, except that we are working with a limited word count here. The trick is to make sure your descriptions are spot-on in accuracy first, before you allow yourself to wander a bit down a poetic road. And when in doubt? Follow Coco Chanel’s advice:

“Before you leave the house, look in the mirror and take one thing off.”

That means: cut, rather than add adjectives or adverbs when you’re editing.

FINALLY …

Know that writing is tough. It’s tough for anyone, even Margaret Atwood. But in addressing that reality, Atwood quotes Samuel Beckett:

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

As always, I’m here if you need me at [email protected]